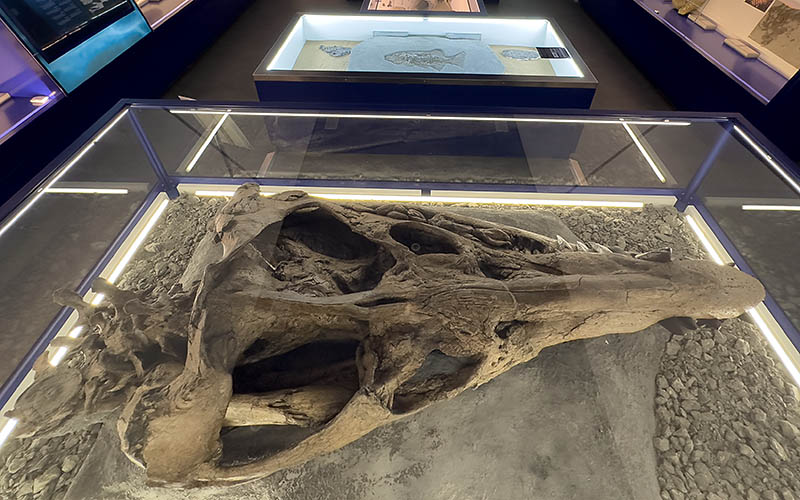

This specimen is particularly important because of its level of completeness and preservation.

The first part of the find – the tip of the snout – was discovered on the beach in April 2022 by fossil hunter Philip Jacobs who then contacted Steve Etches from The Etches Collection Museum in Kimmedridge.

Philip initially thought the find was a piece of wood embedded in the shingle but when he looked closer he realised it was part of a skull. It had fallen out the cliff, tumbled onto the beach and been washed around for a few weeks. It was impossible to pick up so he had to get help; three others, a ladder, plywood and ratchet straps and then the fossilised bone had to be hauled a mile and a half off the beach.

While the initial part of the skull was easily accessible, the rest of it certainly wasn’t.

Wedged into the rocks 11 metres from the ground and 15 metres down from the top of the cliff was the rest of the head and it needed a specialist team and professional climbers to recover it.

The pliosaur had come to rest on its back and it was slightly tilted. Releasing it was very hard and hot work, excavating over three weeks in five hour rotating shifts. The team had to net the cliffs, cut a cave and cover the precious exposed bones with foil and plaster which was then strengthened with wire mesh.

The skull couldn’t be taken downwards so it had to go up in a custom made box created by a local farmer. It was designed to always stay level and to move on skids.

Once out, it was prepared and preserved over 10 months by a specialist team – Steve Etches, Chris Moore, Alex Moore and Tracey Barclay.

The skull was so big it wouldn’t easily fit inside the museum’s preparation room – and it nearly collapsed the table as it was so heavy!

The mudstone had to be cleared off with compressed air pens and then all the bone fragments had to be put back together like a jigsaw. Air abrading was used to finish the skull off and show all its detail.

What they revealed was the most complete and best preserved pliosaur skull to date, and one that could be a new species!

Some of the teeth on the skull had to be recreated as they’d snapped off. A complete tooth was scanned at Southampton University and used to make replicas. This is the only restoration but it shows the full impact of the pliosaur and helps bring it to life.

Pliosaurs were one of the most ferocious Jurassic predators that hunted in the Kimmeridgean sea – their diet included other large creatures such as ichthyosaurs. The marine reptiles lived around 150 million years ago.

It’s the top of the food chain and likely the largest carnivorous reptile that’s ever lived.

It’s thought that this pliosaur was a juvenile, so not yet at full adult size. The skull is substantial – around 2 metres long and containing 130 very impressive teeth which are triangular in shape and very sharp. They’re designed to cut and crush, like predatory reptiles today.

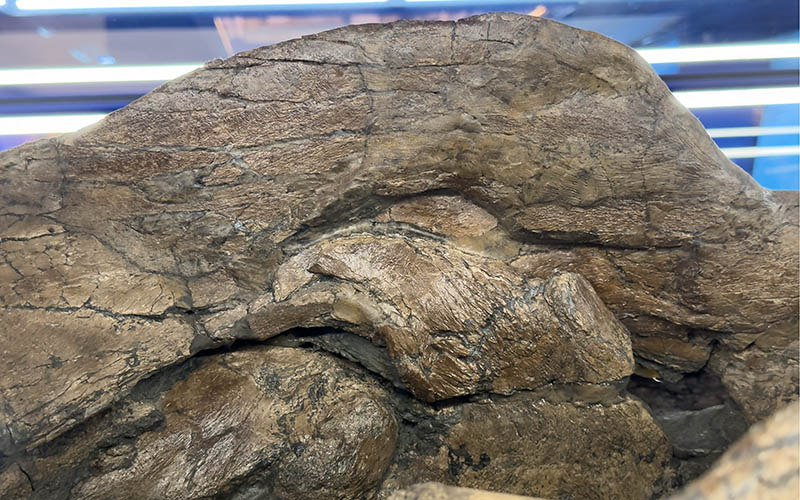

The teeth on the bottom jaw of pliosaurs normally end at the front of the eye socket but on this one they end at the back which point to it possibly being a new species.

This one is also special because of the parietal crest – the raised bit in the middle of the skull just behind the parietal eye – the sensor that would have given indications of light and pressure to the animal. It’s higher than normal so could be another indicator of a new species, but it’s too early to be sure yet. It could also be an indicator of it being a male, but again, more research needs to be done.

It has many pits along the snout which go back in two channels into the brain. They’re like pressure pads to pick up on any movement in the water. They may also help the pliosaur detect electrical discharge from any prey it’s following.

The skull, dubbed Sea Rex, went on display to the public at The Etches Collection on 2 January 2024.

The rest of the body (the postcranial skeleton) is likely to still be in situ and would add another 10 or so metres to the length of the animal.

You can help fund the recovery of the body and be part of palaeontological history by donating to the Rescue Sea Rex campaign on JustGiving.

Steve said: “The excavation of the remaining Pliosaur body is a race against time and nature, so this is a priority for me, especially since we could lose important pieces of the specimen due to rapid cliff erosion.”

The documentary, Attenborough and the Giant Sea Monster was first aired on BBC1 on New Year’s Day 2024. It’s also available on iPlayer. The programme combines ground-breaking science, fascinating natural history with gripping storytelling, and state-of-the-art CGI to explore the tale of the most formidable predator of the Jurassic world.